Review: Lolita (1962)

Cast: James Mason, Shelley Winters, Sue Lyon

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Country: UK | USA

Genre: Drama, Romance

Official Trailer: Here

Editor’s Note: This review of Lolita is a part of Matthew Blevins’s Stanley Kubrick Spotlight.

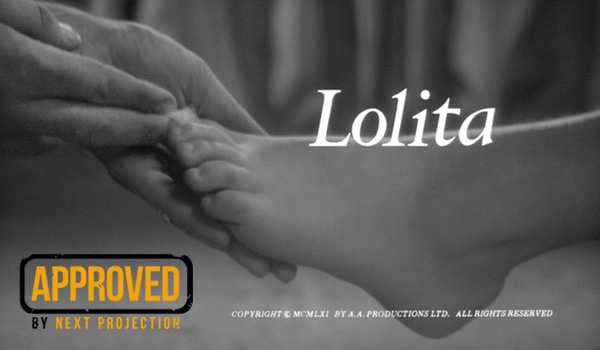

Kubrick sets the stage for his adaptation of Nabokov’s literary classic with nothing more than a foot occupying the frame. Kubrick is (among many things) a visual artist, and in this single unbroken sequence that plays behind the credits he establishes much about the psychological elements behind the story that is about to unfold. The foot is clearly not one of an adult as the proportions aren’t quite fully developed. A man’s hand enters the frame and the characterizing wrinkles and weathered shade quickly imply that this man is much older than the person attached to the foot it gingerly approaches. The opening credits roll as the hand fastidiously and ritualistically applies nail polish with tender affection. We can sense the visual taboo even if we are completely unfamiliar with the story. We know that the action is not being carried out in a socially appropriate way as the hand labors daintily over each stroke of the brush.

The unseen male figure is not acting in a way that we would expect a father to act, nor does it perform its task with any degree of the mature sensuality we would expect between two lovers. This is an imbalanced and inappropriate scenario that is rife with telltale indications of psychological idiosyncrasies. It is clear that this unseen male figure is has an unhealthy obsession with the female that this foot belongs to. The attraction is one of psychological torment and an inappropriate affectation with uncorrupted innocence, a false innocence that exists only in the male’s warped perspective. This succinct visual language is one that only a master filmmaker could employ, and Kubrick is one such master linguist in the unspoken language of film. Kubrick’s adaptations are unconcerned with any sense of obligation to the source material. Once Kubrick has touched something he has permanently imbued it with his presence. Just as A Clockwork Orange no longer belongs exclusively to Anthony Burgess, Lolita no longer belongs solely to Nabokov.

This succinct visual language is one that only a master filmmaker could employ, and Kubrick is one such master linguist in the unspoken language of film.

Kubrick’s version of Lolita is condensed and re-imagined to facilitate the demands of the medium of cinema. It is a noir fable of psychological torment that finds its stark black and white visages in the crumbling baroque, abysmally WASPy, and the classic vision of America that lives somewhere in between. It doesn’t have the luxury of thousands of pages to establish fully formed characters, but it gives us a literary protagonist filled with contradictions and an increasingly tormented psyche. It puts us at odds with ourselves as we fall for the debonair charms of James Mason’s Professor Humbert, only to have those initial perceptions challenged at every turn until we see nothing but the broken shell of a man. The broken protagonist is no stranger to film noir, but the extent and nature of Humbert’s flaws are unusually dark for a major studio production in the early 60s.

Kubrick’s version of Lolita is condensed and re-imagined to facilitate the demands of the medium of cinema. It is a noir fable of psychological torment that finds its stark black and white visages in the crumbling baroque, abysmally WASPy, and the classic vision of America that lives somewhere in between. It doesn’t have the luxury of thousands of pages to establish fully formed characters, but it gives us a literary protagonist filled with contradictions and an increasingly tormented psyche. It puts us at odds with ourselves as we fall for the debonair charms of James Mason’s Professor Humbert, only to have those initial perceptions challenged at every turn until we see nothing but the broken shell of a man. The broken protagonist is no stranger to film noir, but the extent and nature of Humbert’s flaws are unusually dark for a major studio production in the early 60s.

In Kubrick’s version of the story, the narrative is inverted and the final twist is placed at the beginning of the film, further changing the dynamic and separating itself from its source material. We aren’t clued in to the full extent of Humbert’s twisted morality as he murders Peter Sellers’ Clare Quilty in the first few minutes of the film. We only know that Humbert judges Quillty for his alleged indiscretions with a young girl, and that Quilty’s sentence is one of death. In this typical noir scenario we can guess at the dynamic of the protagonist’s flawed moral code, but we are not yet let in on the fact that Humbert is acting in a hypocritical fashion. The suave James Mason gives the character enough charm and credibility that he is able to pass as a morally flawed father figure until he “succumbs” to the advances of Lolita later in the film. In scenes leading up to that point of no return we can guess at Humbert’s intentions, but we are allowed a twinge of deniability that will ultimately be used against us as an affront to our own cultural superficialities.

Kubrick was bound by restrictions that forced him to use heavy-handed innuendo that is more comedic than it is evocative, and quick suggestive glances fill in any blanks. When Mason’s Humbert shows trepidation toward a new living arrangement with Shelly Winters’ Charolotte Haze, Haze entices Humbert with a tour of the garden where Lolita is sunbathing in a bikini. Promises of late night snacks and “et cetera” quickly pique Humbert’s interest, but we do not yet know his full intentions for staying. Does he see Lolita as a daughter figure? Does he choose to stay because he knows he no longer has to be alone with the irritating Charlotte Haze? We quickly find out that his motives have been less than pure from the onset, and that his immediate attraction to Lolita is something that he accepts all too easily, hinting that this isn’t the first inappropriate relationship that he has participated in.

Promises of late night snacks and “et cetera” quickly pique Humbert’s interest, but we do not yet know his full intentions for staying.

Humbert’s obsession will come to define him, and Lolita’s age appropriate immaturity will shake the image of perfection he had defined of her. Lolita is a tragically damaged adolescent that was placed in inappropriate situations far before she was mature enough to process them. In the breakneck pacing of the film as it swoops across time and spaces with the auspicious precision of a pendulum, it is easy to lose track of the fact that Lolita has lost both parents and has been placed in the care of a disturbed pedophile. Perhaps there are cultural superficialities working against us again, and Lolita’s self-assured nature has removed our ability to easily empathize with her plight. Perhaps Kubrick’s inability to show us the darker side of such a scenario has eroded the impact of what the film is only allowed to imply. In any case, Kubrick paints a dark world where altruism is not allowed to breathe, and darkness looms behind closed doors that we are never allowed to open.

Humbert’s obsession will come to define him, and Lolita’s age appropriate immaturity will shake the image of perfection he had defined of her. Lolita is a tragically damaged adolescent that was placed in inappropriate situations far before she was mature enough to process them. In the breakneck pacing of the film as it swoops across time and spaces with the auspicious precision of a pendulum, it is easy to lose track of the fact that Lolita has lost both parents and has been placed in the care of a disturbed pedophile. Perhaps there are cultural superficialities working against us again, and Lolita’s self-assured nature has removed our ability to easily empathize with her plight. Perhaps Kubrick’s inability to show us the darker side of such a scenario has eroded the impact of what the film is only allowed to imply. In any case, Kubrick paints a dark world where altruism is not allowed to breathe, and darkness looms behind closed doors that we are never allowed to open.

Whether we interpret the film as the flawed work of a master director that did the best he could under stifling restrictions, or as a masterclass of tragic noir figures and darkly hilarious social satire is up to us to decide. We shouldn’t really judge it for what it was sourced from or what it could have been if. Its two and half hour runtime flies by at often breakneck speeds, and each frame is packed with the carefully plotted visual beauty that we would expect from Stanley Kubrick. However we choose to interpret it, there is no denying the merits its technical brilliance or the unprecedented nature of its subject matter as a major motion picture of the early 1960s.

Review: Oblivion (2013)

Review: Oblivion (2013) Review: Molly Maxwell (2013)

Review: Molly Maxwell (2013) Review: 42 (2013)

Review: 42 (2013) DVD Review: A Man Escaped (1956)

DVD Review: A Man Escaped (1956) Review: To the Wonder (2012)

Review: To the Wonder (2012)