Our ‘Precious’ Stories: How to Survive Their Film Adaptations

Editor’s Notes: This article is intended for readers who have already seen The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, Life of Pi, and Les Misérables. (If you’ve seen 2 out of 3, by all means skip a section, but we don’t want to ruin 3 great films if you haven’t had the opportunity to experience them yet!). Paul Clifford is a Next Projection guest contributor. You can find more of his work at Eloquent Graffiti.

George Bluestone, the father of criticism in the field of ‘novel to film’ adaptation suggests that, “changes are inevitable the moment one abandons the linguistic for the visual medium” (Novels into Film). Somehow, acknowledging this fact doesn’t make it any easier when we wander into a theatre to view a film ‘based on’ one of our favourite stories! Are there any stories so precious to you that the announcement of a film adaptation causes you to shutter?

As an avid reader and film fanatic, I am routinely in a position to compare two ‘versions’ of a particular story–that presented on the page (or stage) with the ‘big-screen’ version (or film). Admittedly, I often fall into the trap of merely highlighting differences, griping about what was added/left out, and feeling duty-bound to declare one or the other version ‘superior’. Conversations over coffee surround this very topic, and debates frequently occur online following the release of a recent film adaptation. There is no question that we live in an age of convergence with regard to the arts!

Encountering similar stories expressed via multiple mediums can be a privilege and a joy, except when someone sees fit to interpret a story we hold truly dear–one we own–one that matters or has mattered to us for a significant period of time. This past christmas season, I encountered film adaptations of three stories extremely precious to me, and quickly discovered that the casual ‘compare & declare’ behaviours were insufficient when it came to sorting out the complex emotions and intellectual relationships that I shared with these texts. I have been rewarded for the time spent sorting out some of these thoughts. I need not litter cyberspace with further reviews of these films (as regards these three films, I’m far too ‘late to the party’ to do so), but I hope that the conclusions I have reached might stimulate further conversation on the subject of these stories, and perhaps, others that are precious to you.

In his excellent book, Novel to Film, Brian McFarlane identifies two “unhelpful critical attitudes” that regularly surface when we compare a source text to its film counterpart: a) evaluation of the film is based on the implied primacy of the novel (or source text), or b) the film is ‘read’ by someone unfamiliar with the source text, or someone who insists on the autonomy of the film version. Essentially, the novel is immediately deemed superior, or it is ignored/dismissed altogether. Neither acknowledges a ‘convergence’ between the arts, and either ‘reading’ misses out on a fascinating relationship that exists when a beloved story becomes ‘multi-modal’. In the case of the three film adaptations I recently viewed, perceiving the films as autonomous was tremendously difficult due to my familiarity with the source texts, and writing them off as inferior to their textual/staged predecessors would be lazy, and significantly decrease my enjoyment of these latest ‘versions’ of the stories I love. McFarlane is right to dismiss these approaches. Fortunately, he offers some alternatives.

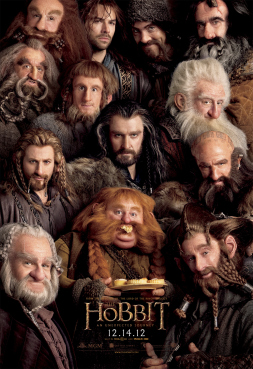

“The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey”

Tolkien fans can not avoid the discussion of ‘fidelity’ as it refers to Peter Jackson’s film adaptations. The degree to which the film is faithful to Tolkien’s text and characters, and the exactness (or not) of his re-envisioning of Tolkien’s elaborate fantasy world are (for many) serious issues treated with a high level of scrutiny–even reverence. While I would certainly not regard myself a Tolkien scholar, I was enchanted by The Hobbit at a young age and have cherished the tales of Middle Earth ever since. I understand why it has taken so long for a live-action adaptation of The Hobbit to storm our multiplexes; family members and copyright holders wanted to be certain that those granted the ‘right’ to produce such a film would demonstrate concern for things such as authorial intent–would aim to ‘get it right’!

Tolkien fans can not avoid the discussion of ‘fidelity’ as it refers to Peter Jackson’s film adaptations. The degree to which the film is faithful to Tolkien’s text and characters, and the exactness (or not) of his re-envisioning of Tolkien’s elaborate fantasy world are (for many) serious issues treated with a high level of scrutiny–even reverence. While I would certainly not regard myself a Tolkien scholar, I was enchanted by The Hobbit at a young age and have cherished the tales of Middle Earth ever since. I understand why it has taken so long for a live-action adaptation of The Hobbit to storm our multiplexes; family members and copyright holders wanted to be certain that those granted the ‘right’ to produce such a film would demonstrate concern for things such as authorial intent–would aim to ‘get it right’!

What we ignore, of course, when we deem to make statements about what the author would have intended (a practice Roland Barthes dismissed decades ago) and estimate the ‘success’ of Jackson’s film, is that our apprehensions of both text and film are merely subjective. As McFarlane reminds us, “reliance on individual, impressionistic comparisons” is unavoidable unless we relocate our critique in a more objective sphere, with the aid of some shared vocabulary. McFarlane employs terminology (originally coined by Geoffrey Wagner) that incites more objective critique, the usefulness of which is clear when it is briefly applied to Jackson’s film, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey.

The first distinction is between elements of a story that can be transposed and those that must be adapted. Often, basic narrative elements are easy to translate directly. Both Tolkien’s novel and Jackson’s film revolve around a hobbit named Bilbo, a wizard named Gandalf, and a band of spirited dwarves that journey far to slay a dragon and reacquire some treasure. This is rather elementary. The structure of the narrative is nearly identical, and quite a bit of dialogue has also been transferred directly from the page to the screen. Much of the action unfolds exactly as it does in Tolkien’s novel, and consequently, feels very ‘true’ to the source material. These instances where translation can be seen are largely due to the fact that narrative elements, words spoken, etc. ‘function independently of medium’.

Other elements such as character, atmosphere, tone, and point-of-view must be adapted (interpreted) to suit the medium of film. When only words are available, the imagination is activated to fill in much of the visual/auditory information that can’t be included. A film director inevitably makes choices about how best to relate these elements utilizing his preferred medium. We may disagree with some of his choices:

* Does Thorin Oakenshield ‘look’ the way you imagined him, or he does he look less ‘dwarvish’ than his counterparts?

* Does the often light-hearted, sometimes comical tone of a novel intended for children survive the change in medium?

* Do sudden shifts in point-of-view not present in the novel serve to needlessly expand a story that was ‘smaller’ on the page?

* How does the atmosphere in Rivendell differ from that in the text and what effect does that change have on our feelings about the elves as we watch the film?

* Do ‘functional equivalents’ available to filmmakers (especially the film’s score) relay mood, suspense, atmosphere to approximate those ascertained by a reader of the novel?

Whether or not we would have chosen to ‘adapt’ the elements above in the manner that Jackson did, we can concede that such decisions were necessary as the story underwent a transformation from novel to film. But what about the choices Jackson makes that resist classification as elements easily translated or forcibly adapted? Scenes never depicted in Tolkien’s text assume quite a bit of screen time: the convening of the White Council at Rivendell, and the episode concerning Radagast the Brown. Another notable insertion is the character of Azog the Defiler, the albino orc that injures Thorin toward the end of the film. A significant amount of background information revealed in pieces throughout the novel is spilled out in a grand ‘Prologue’. Perhaps one of the most significant details is that Bilbo clearly sees Gollum drop the ring; and consequently, Bilbo is aware of his own thievery when he takes advantage of Gollum in the game of riddles and escapes with his prized possession.

Such directorial decisions can only be understood as commentary, wherein Jackson knowingly deviates from the source material, retaining the inspiration that comes from Tolkien’s novel, but re-imagining it in order to produce an entirely new work. Bluestone notes once again that inevitably, “the filmist becomes not a translator for an established author, but a new author in his own right”. In this case, there is little question that Jackson’s motivation is to produce a work that will dovetail nicely with his “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy, and elevate the tone and grandeur of Bilbo’s story, such that it will serve as a suitable companion to those films.

Commentary need not be perceived as strictly negative. I welcomed the focus on ‘home’, and felt that Bilbo’s motivation to press onward was strengthened by the careful identification of the dwarves as a people without a land they could truly call home, without a shire–a sanctuary. Even still, my sense several weeks after first viewing the film is that Jackson feels comfortable enough in the realm of Middle Earth to freely insert elements of commentary when and how he chooses. The truth is, he has been afforded this freedom! Am I pleased with how he has exercised it? Merely satisfied, not thrilled, but McFarlane’s terminology clarifies that while I may be willing to forgive ‘adaptations’ that differ from my previous experience of the story, I am less willing to stomach some of his ‘commentary’.

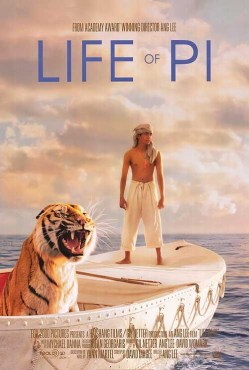

“Life of Pi”

It was with fear and trepidation that I ventured into a late-night screening of Ang Lee’s “Life of Pi” the week before the bulk of the 3D screens in my area would surely be surrendered to Jackson’s aforementioned journey into Middle Earth. I first read Yann Martel’s Life of Pi in 2010, when I was called upon to teach it to a group of eleventh grade English students. What followed was undoubtedly one of the most rewarding months of my teaching career thus far. We examined why certain stories resonate and challenge us, considered Pi’s maturation as it relates to the various names he receives as a child, and debated one’s ability to subscribe to multiple world views simultaneously, and all of that before the shipwreck even occurs 100 pages into the novel! As our study deepened, we explored mankind’s will to survive, contemplated the relevance of prayer in our lives, and entertained the notion that belief can exist independently of–and at times, in spite of–reality. So as I said…though I admire Ang Lee’s films very much, I was terrified that a poor film rendition of this meaningful story could somehow sully the memory of a marvellous educational experience, and render such an experience null and void for future students who would contact the film before (or worse, instead of) the text.

It was with fear and trepidation that I ventured into a late-night screening of Ang Lee’s “Life of Pi” the week before the bulk of the 3D screens in my area would surely be surrendered to Jackson’s aforementioned journey into Middle Earth. I first read Yann Martel’s Life of Pi in 2010, when I was called upon to teach it to a group of eleventh grade English students. What followed was undoubtedly one of the most rewarding months of my teaching career thus far. We examined why certain stories resonate and challenge us, considered Pi’s maturation as it relates to the various names he receives as a child, and debated one’s ability to subscribe to multiple world views simultaneously, and all of that before the shipwreck even occurs 100 pages into the novel! As our study deepened, we explored mankind’s will to survive, contemplated the relevance of prayer in our lives, and entertained the notion that belief can exist independently of–and at times, in spite of–reality. So as I said…though I admire Ang Lee’s films very much, I was terrified that a poor film rendition of this meaningful story could somehow sully the memory of a marvellous educational experience, and render such an experience null and void for future students who would contact the film before (or worse, instead of) the text.

What was I expecting or hoping for this film to be? How could it possibly live up to such grand expectations? Could it match the power of the final chapters as I read them for the first time stretched out on the spare bed in our study? Would it strike a chord the way that it did in our final lesson of the unit when we revisited an earlier exercise and made connections between our stated values, and our beliefs, and what we believe to be ‘true’? How could it? I’m not sure that classifying the director’s choices under headings of transposition or commentary would suffice if the end result struck me as disastrous. Objectivity eluded me.

What I wanted to experience was a film that was accurate and truthful in its depiction of Martel’s story! Gunther Kress uses the term ‘modality’ in his book, Reading Images, to describe ‘the measure of the truth of representation in relation to a predetermined set of standards prescribed by a particular medium’. In other words, modality increases/decreases depending on the degree to which we ‘perceive truth’ in an image–or by extension–a representation of a literary work. Though it goes hand-in-hand with ‘fidelity’, Kress’ term acknowledges the inevitable existence of subjectivity that results from expectations of the viewer and differences in perception. I would be lying if I tried to deny my high expectations of any filmmaker who dared to adapt this novel. In the case of Lee’s film, and according to the subjective judgments of this viewer, modality is accomplished if three conditions (predetermined standards) are met:

1. Richard Parker, the formative bengal tiger, must feel entirely ‘real’ from his first appearance floundering in the water, to his eventual disappearance into the tall grass. There is no room for this ferocious beast to be ‘Disneyfied’. Pi’s constant danger must be vivid and frightening, and the technology that allows a young actor and a tiger to appear in such close proximity must be completely invisible.

2. The exposition can not not be rushed in favour of the action that follows. The first 100 pages of Martel’s novel contain the ever-important promise (“I will tell you a story that will make you believe in God”) and pave the way for Pi’s extraordinary ability to survive such a wretched ordeal. The temptation to compress an essential introduction and skip ahead to the action is understandable, but would ultimately prove detrimental.

3. The ‘better story’ should be self-evident. The power of a story is unleashed in its telling, and what a first-time viewer won’t realize is that for the bulk of the film we observe the first of two narratives explaining Pi’s survival. His hospital visitors–and the audience–will be invited to decide which story to ‘believe’! If the audience doesn’t buy in, if the ‘one with the animals’ isn’t believable, then Martel’s promise is broken.

Though I will always have a greater appreciation for the source text due to my memorable initial contact with it, I believe that Ang Lee’s film meets and occasionally surpasses the conditions (expectations) described above. At no time was I distracted from the story to marvel or grimace at the CGI tiger; I just accepted it as entirely real. Lee definitely tweaked but obviously recognized the importance of Martel’s extended exposition and did it justice. I felt shivers as lines of dialogue were ‘transposed’ directly in the final scenes of the film, and I had a strong ‘sense’ throughout that characters/plot/themes were depicted ‘truthfully’. Kress would remind us that in addition to our personal sense of ‘modality’, comes a cultural one, and I have been pleased to confer with others who perceived the film similarly and are as passionate about the source text as I am. Merely understanding Kress’ analytical lens does not equip us to prove that the film is or is not ‘highly modal’, but we can relish the fact that if it feels like the filmmaker ‘got it right’, it is because we have identified a representation that ‘appears truthful’.

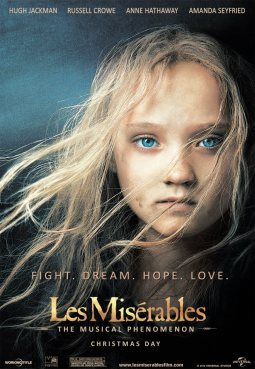

“Les Misérables”

So it seems a bit contradictory I suppose to attempt an ‘objective’ evaluation of Jackson’s “The Hobbit” only to embrace the ‘subjectivity’ inherent in Kress’ explanation of modality as it applies to “Life of Pi”. Perhaps it is simply honest to acknowledge this tension that constantly interferes with our ability to offer valuable critique of cherished stories retold in different forms. How then am I to understand my enthusiasm for Hooper’s rendition of Victor Hugo’s tragic tale? I would argue that Hooper’s film improves upon the beloved stage musical, but can I defend such a claim?

So it seems a bit contradictory I suppose to attempt an ‘objective’ evaluation of Jackson’s “The Hobbit” only to embrace the ‘subjectivity’ inherent in Kress’ explanation of modality as it applies to “Life of Pi”. Perhaps it is simply honest to acknowledge this tension that constantly interferes with our ability to offer valuable critique of cherished stories retold in different forms. How then am I to understand my enthusiasm for Hooper’s rendition of Victor Hugo’s tragic tale? I would argue that Hooper’s film improves upon the beloved stage musical, but can I defend such a claim?

Andre Bazin nails it when he claims that “faithfulness to a form, literary or otherwise, is illusory: what matters is the equivalence of meaning of the forms” (“Adaptation, or the Cinema as Digest”). I loved Tom Hooper’s “Les Misérables”, and will continue to say so despite the backlash it now appears to be enduring! Bazin’s statement truly sums up my sentiments: the profoundly affecting story that has twice enraptured me from the stage did so again on the big screen! It’s that simple. We live and breathe and cherish stories because they have meaning, not out of reverence for their form!

The unjust punishment, spiritual defeat, forgiveness, and rebirth of Jean Valjean is truly epic, though it accounts for at most a quarter of the tale depicted on screen in Hooper’s “Les Misérables”. What follows is the story of a man raised out of the mire to become an upstanding gentleman, a compassionate father, and a merciful opponent. His nemesis, the incomparable Javert, refuses to accept the forgiveness and mercy that have proffered Valjean a second chance at life, and ultimately plummets to his death due to his inability to reconcile the man before him with the false image of that man that has haunted him for decades previous. Fantine is a pillar of suffering, a hopeless victim dealt blow after blow, who wishes only that her child will find light in a world consumed by pain. Cosette is that rescued child, cherished by an honourable father figure who cares for her and knows when best to release her into the hands of a man who will show her the romantic love she deserves. Marius, and his idealistic friends on the barricade, long for a future free from tyranny, full of opportunity, and worthy of the love they possess. I could expound the virtues of the story forever. I could quote my favourite lyrics. Melodrama? OK…but damn powerful stuff regardless of your desired label!

I have puzzled for a couple of weeks now over how to adequately describe the heightened impact of these characters and this narrative as it was expressed on film. Yes, the actors sang live on set and this directorial choice has been championed, but also criticized due to the less-than-perfect vocal performances that resulted. In truth, if vocal perfection was all that mattered in communicating the story, a cast full of the world’s best professional singers would have sufficed, but Hooper was willing to sacrifice musical sublimity in favour of screen actors whose gaze would penetrate our souls as they sang “I Dreamed a Dream”, “Bring Him Home”, or “Empty Chairs at Empty Tables” in extreme close-up. Much has also been made of their gaze…at times directly into the camera, a cardinal sin for any screen actor, seasoned or otherwise. I contend that it is precisely this ‘adaptation’ that elevates Hooper’s “Les Mis” above its stage counterparts.

I began this overlong post with the premise that consideration of stories and how they are adapted is especially relevant because we live in an age characterized by the ‘convergence of the arts’. As actors sing and agonize and shed tears while staring into the camera, we are audience to a film AND a stage musical simultaneously. We are immersed in sequences especially ‘filmic’ as the camera winds through the slums or captures the chaos of battle in the streets, but when Anne Hathaway lets loose her despair in song, she is singing to US! Who else would be listening? She’s alone. This is the artifice of the musical genre; she is singing her thoughts for our benefit. On stage, she would address the audience and occasionally lock eyes with audience members in the front row. Hooper’s film puts all of us in the front row–closer, in fact! He puts us close enough to reach out and catch the tears streaming down her cheek, then pulls back to remind us that we are only witnesses. We can share her sorrow but do nothing to alleviate it despite how near to us she appears to be.

Kress and Van Leeuwen maintain that “[i]n the visual semiotics of Western cultures, images are used to perform two fundamental types of ‘image act’: demands and offers”. They argue that every image (moving and otherwise) ‘offers’ a being/object for the viewer’s contemplation, or ‘demands’ an immediate social response–invites the viewer into a specific social relationship. Which effect is accomplished by a given image is determined by an assessment of the vectors ‘formed’ by the subject portrayed, or the angle from which the subject is captured.

Vectors, however, are defined by the line-of-sight of an image’s subject, and enable us to delineate between implied offers/demands by distinguishing where exactly the subject is ‘looking’. A ‘demand’ is ascertained if a subject looks directly at the viewer, and the nature of that demand (and the implied relationship between subject and viewer) is to be apprehended by the manner in which the represented subject ‘looks’. An offer, conversely, is understood when the ‘participants’ or objects represented in a given image do not gaze at the viewer in a definable way. They are, consequently, depicted for the viewer’s inspection, but do not require acknowledgement from the viewer or incite a specific social response.

When Fantine, Valjean, or Marius look at us, they demand a response, some type of acknowledgement, a relationship!!! Whereas most characters depicted on film gaze past us and offer themselves for scrutiny, Hooper’s carefully chosen actors with the occasionally weak voices convey their emotions directly with an intentional gaze. Though cloaked in theoretical jargon, this simple model for understanding how images communicate meaning validates the tears I shed involuntarily at two points in the film (yup! I’m secure enough to admit this!) Hooper undoubtedly harnessed the greatest strengths afforded by both stage performance and film and united them to maximize the power of his subject matter. Somehow my knowledge of what would happen next evaporated as he immersed me wholly in the events of his film. Clearly, I’m in subjective territory at this point, but I believe that the transformation from stage to film intensified the meaning!

At one time or another, we all yearn to see and hear our favourite stories, but this desire is tempered by an even stronger desire to see them treated with care and respect–to ensure they are preserved. Brian McFarlane contends that the goal of a director who seeks to deliver a “faithful film version” of a text is to “achieve, through quite different means of signification and reception, affective responses that evoke the viewer’s memory of the original text”. Fidelity, truth, meaning, and memory matter to us, and if nothing else, perhaps we have thought a little more about why!

What stories are ‘precious’ to you? How have they fared on the big-screen? I’d be honoured if you shared.

**Feel free to contact me if you would like a complete list of sources quoted in this piece.

-

http://twitter.com/Bryan_C_Murray Bryan Murray

DVD Review: A Man Escaped (1956)

DVD Review: A Man Escaped (1956) Review: To the Wonder (2012)

Review: To the Wonder (2012) Review: Upstream Color (2013)

Review: Upstream Color (2013) Review: The Company You Keep (2013)

Review: The Company You Keep (2013) Review: The Place Beyond the Pines (2012)

Review: The Place Beyond the Pines (2012)