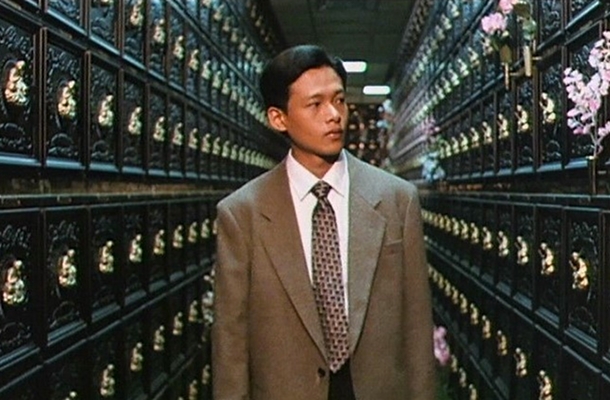

TIFF’s Century of Chinese Cinema Review: Vive L’Amour (1994)

Cast: Chao-jung Chen, Kang-sheng Lee, Kuei-Mei Yang

Director: Tsai Ming-liang

Country: Taiwan

Genre: Drama

Official Trailer: Here

Editor’s Notes: The following review of Vive L’Amour is part of our coverage for TIFF’s A Century of Chinese Cinema which runs from June 5th to August 11th at TIFF Bell Lightbox. For more information of this unprecedented film series visit http://tiff.net/century and follow TIFF on Twitter at @TIFF_NET.

A forgotten key opens doors to unattainable dreams in Ming Liang Tsai’s Vive L’Amour. In the midst of the unceasing movements and abrasive sounds of Taiwan this key offers sanctuary for the lonely denizens of humanity that are unable to thrive in the overbearing restraints of a city imprisoned by ocean. A young man briefly breaks the fourth wall as he looks into a convenience store mirror, primping for some nonexistent encounter in a gesture of listless vanity looking desperately into the eyes of the audience, unable to find companionship in the cinematic vision of Taiwan that Tsai has trapped him in. Love is the unattainable dream for the lonely Hsiao-ang, but he is not alone in his desire for connection. In Ming Liang Tsai’s Vive L’Amour meaningful connection is the unattainable collective dream for three weary urban inhabitants. They are all bereft of identity in the overcrowded and ever-shifting cityscapes of a ceaselessly changing Taiwan, starved for love but unable to achieve it because of the impositions of their shared environment.

In the midst of the unceasing movements and abrasive sounds of Taiwan this key offers sanctuary for the lonely denizens of humanity that are unable to thrive in the overbearing restraints of a city imprisoned by ocean.

The dynamic of two men and one woman is often used in the films of Tsai, each man representing opposite sides of the male psyche but typically limited by the parameters of their environments rendering their empty attempts at creating an individual identity impossible. The pensive uncertainty of Hsiao-ang and brash outward Westernism of Ah-jung ultimately leave the same invisible trace on a city that is in constant turmoil with itself, unable to settle on one identity as it is constantly torn down and rebuilt. Ah-jung masks himself in the trappings of Western notions of “cool” as he sports his leather jacket, cigarettes, Budweiser, denim, and the ascribed false outward confidence that he’s likely compiled from movies. Hsiao-ang harbors a secret infatuation for Ah-jung and the false freedom and counterfeit confidence that he exudes, but both are trapped by their inescapable and stifling surroundings. Mei, a female character inadvertently intertwined in the lives of the opposite males would be a central source of conflict in Western cinema, but in Vive L’Amour she undergoes her own crisis of identity as her attempts to unload undesirable property in her job as a realtor offers the same ephemeral satisfaction as her sexual trysts with the falsely assertive Ah-jung. Their chance encounters and unknown connections bind them in their shared ennui of urbanization, but Tsai would never make a cinematic concession that would exploit these connections for cheap emotional payoffs.

Tsai uses audio to further isolate these characters in the incessant murmur of their urban surroundings. The only respite from the constant noises of traffic and construction is within the walls of the uninhabited real-estate that Mei is tasked with selling despite its undesirable and half-finished nature. In addition to sparse dialogue and richly emotive sound, Tsai frames the characters as merely elements of the overall picture, often offering a Ford’esque window into the outside world through doorways that show the inescapability of the ceaseless city traffic. When characters find refuge from their chaotic urban surroundings, sound again becomes more intimate and deliberate. Silence is a luxury that is rarely attainable in the city, and Tsai relishes these moments of silence as his characters are granted brief asylum from their unknown source of torment and neurosis.

These characters cannot escape that which torments them no more than they can articulate the source of their existential agony. They seek nature in unnatural surroundings, submerging themselves in water, relishing in the multitudinous joys of watermelon…

These characters cannot escape that which torments them no more than they can articulate the source of their existential agony. They seek nature in unnatural surroundings, submerging themselves in water, relishing in the multitudinous joys of watermelon (a theme Tsai would explore more directly and explicitly in Wayward Cloud), walking through muddy bastardized green-spaces, implement bird-chirping doorbells that remind visitors that the sound of birds existed before the omnipresent noise of city traffic overtook every outdoor noise, and rooster alarm clocks that suggest a kitschy affection to bygone agrarian lifestyles. They consume their meals in little orderly boxes and designate time in their busy schedules to have emotional meltdowns in amphitheaters, a place where tears and desperate cries can vanish in the wind so one can regain composure and continue drudging through a life that feels devoid of meaning. The characters’ personalities are as unsettled as their surroundings, in a perpetual state of unrest as buildings are built and rebuilt, creating a dichotomous Taiwanese landscape where old clashes with new. These characters are unable to forge an identity that successfully merges these conflicting ideals. Theirs is an identity that mirrors the unrest and diversity of the environment in which they live, devaluing verbal communication in a city that never stops speaking, fearful of change in a city that never stops building and rebuilding, and fearful of connection in a population that offers endless opportunities for companionship.

Ming Liang Tsiang’s Vive L’Amour shows us that isolation can occur in the most densely populated areas, and fear of love may hamper us from ever forming a real connection with someone because of our secret affinity for isolation and fear of exposing and sharing our flaws with others. Even in the restlessness of an ever-changing Taiwan characters seek isolation. Whether they are bathing themselves in the waters of Tsai’s reflectively drab bathrooms or crying into the wind; they seek escape from their surroundings but have no idea where to go. They don’t realize that they are tormented by an unsettling city in constant flux, nor do they suspect the possibility that there may be someone hiding under the bed that shares in their thoughts and dreams and could offer a meaningful connection through shared neuroses.

Related Posts

![]()

Matthew Blevins

![]()

Latest posts by Matthew Blevins (see all)