The Trilogy of Before Sunrise, Sunset, and Midnight

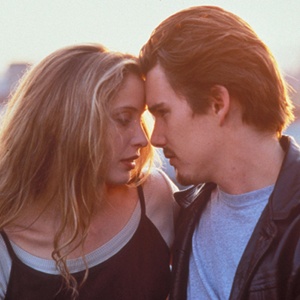

The trilogy of Before Sunrise, Sunset, and Midnight could only work as cinema. Or rather, it might work in another medium, but the effect would not be the same. In each, the American writer Jesse and the French activist Céline meet and have lengthy conversations in European settings, Vienna, Paris, and the Greek Peloponnesus, respectively. Nine years span between installments, both in film time and actual time: 1995, 2004, and 2013. And, obviously, with each near-decade, Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy age along with the protagonists they play. Before Midnight is, of the three movies, the most aware of this aging process, and Richard Linklater, director and co-writer, along with his two actors, takes advantage of certain specific features of cinema: films are frozen and infinitely repeatable time. We can watch Hawke and Delpy in 1995, over and over again, and when we see them in 2013, there is a story inscribed on their faces and bodies that goes beyond acting. They are older, and that is not only the theme of the script, but a physical fact. And we are older, too.

The trilogy of Before Sunrise, Sunset, and Midnight could only work as cinema. Or rather, it might work in another medium, but the effect would not be the same.

In Before Sunrise, young Jesse and Céline meet on a train and decide to spend a day walking around Vienna. After roughly 24 hours, they promise to meet again next year. In Sunset, we learn they ended up missing each other. Jesse, instead, has written an autobiographical novel about his Viennese encounter, and when he presents it in a Paris bookstore, Céline pays him a surprise visit. Now in their thirties, with a number of frustrated relationships and marriages behind them, both of them exorcise their tortured memories during a Parisian stroll. In Céline’s apartment, as Céline awkwardly sings a tune, she reminds Jesse that he will miss his plane. He sits back with a smile and replies that he knows and doesn’t care. Midnight, then, has them both together and with children, living in Paris and vacationing in Greece.

Unlike the prequels, it begins, not with a meeting between Jesse and Céline, since they are already together, but with a departure: to be with his French girlfriend, Jesse has had to leave behind his American wife and child, and his distance from the latter is painful and irresolvable. His son spends summer with him in Greece, but as he still lives in the United States, a return trip is inevitable. When the movie opens, both are inside an airport. Jesse is nervous, anticipating the coming separation. He complains to his son that he never tells him much. The teenager boy is going through that phase where parents recede into the background, while the foreground of experience is taken up with girls, questions about the future, doubts about self-esteem and personal worth, and other things of that nature. Jesse understands, at some level, but grows increasingly restless. His son is becoming independent, and Jesse was never there during his years of dependency, during his childhood, and now it might be too late to ever really be his father.

Outside the airport, Céline waits in the family car, along with the two daughter she has birthed and raised with Jesse. When he returns and drives away, as the girls sleep, Céline and Jesse slip back into the mold of the trilogy, chatting in prolonged unbroken takes. This is a self-conscious return to the series’ roots, punctuated by the belated appearance of the movie’s title. Before Midnight is, in part, an analysis of the previous films. We already know Jesse wrote a book recounting the plot of Sunrise, and now we learn he produced a sequel, more or less about the events of Sunset. Also, Céline and Jesse continually reassess their memories of both their Viennese and Parisian encounters, prompting us to do likewise with our recollection of the movies. Relationships are stories we tell to others and ourselves, images we constantly return to, changing their meaning with time. They are also fragmented stories, splintered by different entrance points. Sunset and Midnight were written by Linklater, Delpy, and Hawke (though Sunrise was written by Linklater and Kim Krizan), and each perspective adds another angle to the overall narrative. There are various levels of authorship, and besides the actors and the director, we can also think of the characters as authors, not only Jesse, who actually writes books, but Céline, who comments on these books and provides addendums or corrections, which often end up being as flawed and personal as the novels themselves, and even us in the theater, who have watched the other movies and have seen what is described in the books, and who therefore have other valid opinions on what Jesse and Céline are debating about, although our vision is filtered through the lens of Linklater.

Nevertheless, despite this complex framework, none of the films become entangled on the threads of meta-narrative gamesmanship, and are rather joyful or mournful, depending on the situation.

Nevertheless, despite this complex framework, none of the films become entangled on the threads of meta-narrative gamesmanship, and are rather joyful or mournful, depending on the situation. Midnight is about how nothing is solid or certain, how relationships can break apart and how what we remember can suddenly either vanish or become redefined. Céline mentions, in one scene, how she used to believe in eternal, transcendent love, something she could count on to persevere. And now, she cannot hold on to anything, not love, not even her values. She receives an offer to work for the government, to continue her environmentalist struggle within a more official context, and though the young Céline would have turned down the job, refusing to become part of the system, this older version of her is not so idealistic and is willing to compromise. Her love for Jesse is similarly complicated, as nine years of relationship and children have worn both of them down. Suddenly, what we saw in Sunrise and Sunset, and especially in Sunrise – where both Céline and Jesse represented, to each other, a utopia of endless romantic possibility –, acquires a completely new shade. Now, those movies we watched so many years ago have been transformed into bittersweet snapshots of youthful promise, repurposed and recycled by Midnight.

Each installment in this series has, as it were, devoured the previous entry, utilized it for its own means. Sunset employed Sunrise as back-story and unmasked it as naïve and innocent. As charming as the single magical day portrayed in the latter might be, it could not remain unspoiled by the disappointments confessed in the former. The magical day becomes, not something to cherish on its own, but a shadow, an unanswered question. It becomes contaminated by what follows it, because in its perfection it seems to unravel the imperfections that inevitably came afterwards. Céline and Jesse experienced bliss in Sunrise, and much of Sunset is spent discussing how the ensuing nine years measured up. Since they once found happiness in each other, they both figure that they might find it again if only they would remain together in Paris.

Each installment in this series has, as it were, devoured the previous entry, utilized it for its own means.

Midnight, quite brilliantly, does not altogether dash the hopes of Céline and Jesse. They have actually achieved a successful relationship together, and many of their exchanges are lively and humorous. Both are obviously in love with each other. What has changed, however, in comparison to the previous movies, is that there is no longer an obvious escape from the present. Sunset had plenty of pain and regret, but Céline and Jesse provided, to each other, alternative visions of the future. Now, in Midnight, there is no clear path ahead, especially if their relationship falls apart. They might reconstruct their lives, but what shape it might acquire, and how long it will take until they do so, is unknown. Over the years, dozens of tiny annoyances have accrued on their shoulders. She is in charge of all the housework, feels overworked and tired. He spends most of his days writing, perpetuating his typically reflective mood. They operate at varying speeds, and although he frequently travels and tours with his books, he mostly remains home while Céline is always on the move, jutting to and from her workplace. She is all energetic desperation while he’s lead-footed and composed, and although this contrast helps them survive together – if both were like Céline, they would kill each other, and if both were like Jesse, they would bore each other – it is also a source of conflict.

Above all, they are anxious about time. Despite the fact that Jesse has, essentially, made Sunrise and Sunset into novels, these could not compare to the films, because the films captured the time of their production. Linklater, Delpy, and Hawke have given us versions – endlessly repeatable and rewatchable versions – of what Céline and Jesse can only remember or reimagine on the pages of a book. Yet, despite this illusion of permanence – the magical day can be replayed time and time again – the overall feeling is one of transience. All three films show us conversations dealing with what happened in the past. Almost nothing happens in any of them, except the unspooling of memory, so that the present they show us appears to evaporate. Midnight, to a greater extent than Sunset, is about this conflict between the storytelling we watch, filmed by Linklater, and the dark continents hinted at by the dialogue, as Céline and Jesse disagree on the particular of what transpired between Sunset and Midnight. We have missed much about their relationship, and the time we have spent with them, profound as it might have been, is inadequate. Midnight owns up to the fact that we cannot really know a human being in the span of two movie hours. What we are left with, beyond what is projected on the screen, are interpretations and clues, mostly dropped by Céline and Jesse as they try to define themselves and each other. Their anguish about the time they will never have back, is partly our anguish about all we still have to learn about this couple, and which will forever remain unsaid in the interstices between Sunrise, Sunset, and Midnight. We feel the time allotted to us, as spectators, is not enough, and we have to be satisfied with the crumbs our hopes have left behind.

Related Posts

Guido Pellegrini

Latest posts by Guido Pellegrini (see all)

- The Trilogy of Before Sunrise, Sunset, and Midnight - August 14, 2013

- Review: Pacific Rim (2013) - July 27, 2013

- Review: Fatherland (2011) - February 16, 2013