Review: All is Bright (2013)

Cast: Paul Giamatti, Paul Rudd, Sally Hawkins

Director: Phil Morrison

Country: USA

Genre: Comedy | Drama

Official Trailer: Here

Editor’s Note: All is Bright is now open in limited release and on VOD

It’s clear in its final act, when layabout comedy gives way to a pseudo-heist story, that All Is Bright isn’t home to the finest plotting we’ve seen this year. Yet whatever weird and wildly inadvisable certain turns this new movie—the latest from Junebug director Phil Morrison—may take, it is, much like its lead character, acting with the best of intentions. He, a dour ex-con who arrives home to find his wife in the arms of the ex-partner to blame for his arrest and his daughter informed he’s fallen to cancer, is an understandably embittered soul, only slightly less cold than the New York streets to which he and hid former accomplice take to sell Christmas trees.

Yet whatever weird and wildly inadvisable certain turns this new movie—the latest from Junebug director Phil Morrison—may take, it is, much like its lead character, acting with the best of intentions.

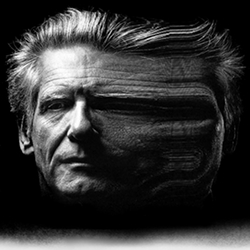

If it seems the setup for a standard Odd Couple-esque comedy, it shouldn’t: Morrison, working from a script by newcomer Melissa James Gibson, delivers a far more cynical product than might be expected. That’s mostly the effect of Paul Giamatti, whose barked delivery and wiry facial hair, for all its effectively aggressive humour, brings with it a desperate sadness to his character. Here is a man truly without prospect, his family gone without chance of return, his financial future pegged on the sympathies of a former friends he loathes. It’s that loathing that lends All Is Bright its tone; Giamatti and co-star Paul Rudd certainly service the inherent wit of Gibson’s script, but so too is its unabated anger conveyed.

If it seems the setup for a standard Odd Couple-esque comedy, it shouldn’t: Morrison, working from a script by newcomer Melissa James Gibson, delivers a far more cynical product than might be expected. That’s mostly the effect of Paul Giamatti, whose barked delivery and wiry facial hair, for all its effectively aggressive humour, brings with it a desperate sadness to his character. Here is a man truly without prospect, his family gone without chance of return, his financial future pegged on the sympathies of a former friends he loathes. It’s that loathing that lends All Is Bright its tone; Giamatti and co-star Paul Rudd certainly service the inherent wit of Gibson’s script, but so too is its unabated anger conveyed.

“Shut up,” Giamatti snarls at one point, gruffly repeating himself over and over again every time Rudd makes to open his mouth. It’s as much an indication of the movie All Is Bright wants to be as it is an encapsulation of the relationship between these characters: Giamatti, in full-on Sideways black comedy mode, easily overpowers the broad antics of his fellow Paul. Yet that’s not to say it’s a film fraught by the tension between contrasting comic styles; this awkward clash is the essence of the movie, not its undoing. Morrison manages to use the more conventional leanings of Rudd’s comedy both to gesture at the generic effort this could be and to gleam some scarce sense of levity amidst bitter bleakness.

Amusing as it is to spend time in the company of these characters, there’s little more to the movie than observing their uneasy interactions, despite its efforts to tie things to current economic circumstances and act as an extreme extension of the difficulty of paternal provision in cash-strapped times.

Where the film fails, amidst no shortage of minor comic successes, is in using its effective dynamic to delve deeper into the story at hand. Amusing as it is to spend time in the company of these characters, there’s little more to the movie than observing their uneasy interactions, despite its efforts to tie things to current economic circumstances and act as an extreme extension of the difficulty of paternal provision in cash-strapped times. That’s how we find ourselves at an uneasy end as suspect as it is sudden, born less of a natural progression of events than it is of the need—finally—to say something. It’s as though Gibson and Morrison suddenly realise the limitations of their focus and rush to heap commentary atop comedy, leaving their film to end with an awkwardly out-of-place addendum.

Where the film fails, amidst no shortage of minor comic successes, is in using its effective dynamic to delve deeper into the story at hand. Amusing as it is to spend time in the company of these characters, there’s little more to the movie than observing their uneasy interactions, despite its efforts to tie things to current economic circumstances and act as an extreme extension of the difficulty of paternal provision in cash-strapped times. That’s how we find ourselves at an uneasy end as suspect as it is sudden, born less of a natural progression of events than it is of the need—finally—to say something. It’s as though Gibson and Morrison suddenly realise the limitations of their focus and rush to heap commentary atop comedy, leaving their film to end with an awkwardly out-of-place addendum.

And yet through it all, Giamatti prevails; the film has the sense to close on his face, which has the capacity to contort itself into a shape that would solve the issues of any finale. In the ravenous rage of this character, barely buried beneath the schlubby exterior, there is the emotional resonance to salvage All Is Bright in its dying moments. With Rudd by his side, there is the humour to get it there in the first place. Whatever the dissatisfaction along the way, be it the slightly wasted supporting turn of Sally Hawkins or the aforesaid lack of any overarching meaning, Morrison’s movie remains an oddly engaging effort; like its hopeless antihero, an underdog that can’t but be supported for all the wrong he does.

Related Posts

![]()

Ronan Doyle

![]()

Latest posts by Ronan Doyle (see all)