The Game of Gravity

Editor’s Notes: Gravity is now out in wide release.

Alfonso Cuarón makes videogames we cannot control, which is what makes his movies exciting. In Children of Men, the most famous scene comes near the end, while the camera follows Clive Owen through British ruins. We watch his back as he ducks through the chaos of urban warfare, and we might almost visualize ourselves with a controller in our hands, advancing our avatar in a third-person adventure game. Cuarón’s long takes contribute to this effect, since many videogames are essentially made up of unbroken takes interrupted by game over screens. Children of Men came close to this concept and Gravity fulfills it.

Alfonso Cuarón makes videogames we cannot control, which is what makes his movies exciting.

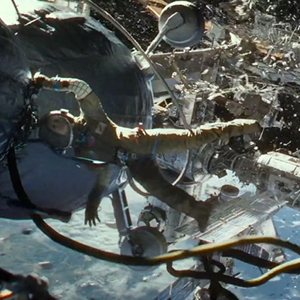

The latter’s computer generated wizardry, of course, echoes the balletic docking sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The camera swings and sways, rotates around gyrating objects. Kubrick focused on spaceships while Cuarón prefers bodies, but the idea is the same in both. Technology is doubly emancipating, facilitating both space travel and the special effects required to represent it. Nevertheless, both movies are also cautionary tales about our love for technology. 2001 features a killer computer that interprets its orders too literally and obeys through murder. Gravity, instead, depicts what happens when a satellite is haphazardly blown to bits for careless reasons, leading to a destructive chain reaction as the orbiting wreckage consumes everything in its path, including the space shuttle carrying astronauts Ryan Stone and Matt Kowalski. The point being, of course, that there is enough manmade material in low Earth orbit (LEO) to produce a chain reaction in the first place: what is known as the Kessler syndrome, further collisions producing more stray objects and more collisions.

The latter’s computer generated wizardry, of course, echoes the balletic docking sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The camera swings and sways, rotates around gyrating objects. Kubrick focused on spaceships while Cuarón prefers bodies, but the idea is the same in both. Technology is doubly emancipating, facilitating both space travel and the special effects required to represent it. Nevertheless, both movies are also cautionary tales about our love for technology. 2001 features a killer computer that interprets its orders too literally and obeys through murder. Gravity, instead, depicts what happens when a satellite is haphazardly blown to bits for careless reasons, leading to a destructive chain reaction as the orbiting wreckage consumes everything in its path, including the space shuttle carrying astronauts Ryan Stone and Matt Kowalski. The point being, of course, that there is enough manmade material in low Earth orbit (LEO) to produce a chain reaction in the first place: what is known as the Kessler syndrome, further collisions producing more stray objects and more collisions.

Kubrick and Cuarón, then, take advantage of the most advanced filmmaking technology available to them in order to comment on technology. Their waltzing cameras observing spinning vessels and space stations are an instance of technology acknowledging itself. More so than in Children of Men, Cuarón’s camera in Gravity is often not chained to any character in particular. Which weakens my earlier analogy, since videogame cameras are not usually so freewheeling (1), except Cuarón is not aping videogames. Rather, he’s doing certain things that they have been excelling at for decades.

Kubrick and Cuarón, then, take advantage of the most advanced filmmaking technology available to them in order to comment on technology.

A given area is fragmented by rapid editing, while an unbroken take travels across it and ties it together. Gus Van Sant, in an interview for the magisterial television special The Story of Film, admitted that his long takes in Elephant, tracking students down school hallways, were inspired by Tomb Raider. Specifically, he was intrigued by the fact that videogames force you to be aware of geographical distance. To move from one point to another, it is often necessary to walk or run. Jumps cuts are not always available to expedite the journey. Curiously, art house aesthetics of duration and monotony, relatively rarified in cinema and reserved for the festival circuit, are conventional in videogaming. A title about a nameless protagonist who walks through an island and hears random voices that might be ghostly murmurs, narration, or memories, had it been a film, would have probably been identified as experimental or avant-garde. Now, release it as a videogame, call it Dear Esther, and it’s a sensation. Yes, many videogamers hated it and don’t even consider it a videogame. And it wasn’t exactly the highest grossing title of that year. But it likely made more money than most experimental films ever have. Videogamers, I suspect, are more accustomed to long stretches devoid of plot or character development, in which the environment speaks for itself. Sure, they are also accustomed to shooting down droves of aliens, foreigners, and other disposable entities. Yet eventless wandering and exploration are common in this burgeoning medium.

Now, long takes in cinema have existed long before videogames. By the time early computer scientists started fiddling with triangular spaceships (2), Miklós Jancsó, that crazy Hungarian, had already made a name for himself capturing breathtaking choreographies of soldiers and peasants in impossibly elegant takes. What is intriguing, nowadays, is that the art of the cinematic long take is beginning to learn a trick or two from videogames. Indeed, the technology behind both is often nearly the same. Children of Men employed some minimal CGI to accomplish its marvelous tracking shots, while Gravity is nothing but a long-running digital spectacle. Jancsó had to deal with a tangible camera; Cuarón and his cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki simply imagine it. CGI cartoons have been doing the same thing, most notably Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin.

With such computerized assistance, the camera can go where it has never gone before. It can encircle characters and even imitate their eyes. Numerous times in Gravity, we see what Dr. Ryan Stone is seeing, and the result is very much like footage from a first person videogame, as we see her hands struggling with slippery ropes. Point-of-view shots are frequent in cinema, although they are not meant to be taken literally. They mimic a character’s perspective, not reproduce it exactly. However, the 1947 noir Lady in the Lake was famously shot from a consistent first-person perspective. More recently, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly envisioned how it might look like to see out of a single functioning eye. The difference between these two movies and the traditional point-of-view shot is that the former replicate the actual physical presence of the character, not just his or her sightline. When the paraplegic protagonist in Diving Bell and the Butterfly receives drops of ocular lubricant, these fall directly onto the camera lens. Cuarón is similarly creative. In order to survive, amidst the fury of clashing spacecraft, Dr. Ryan has to be aware of her surroundings. She must find her colleagues, grab onto handholds and lingering scraps of metal, and maneuver past incoming debris. Her environment, always threatening to annihilate her, is also her only possibility for salvation. If she fails to find what she seeks, she is doomed. We watch her desperation through her searching eyes, so that Gravity, to paraphrase Martin Scorsese, is about what is in the frame and what is out of it.

Her environment, always threatening to annihilate her, is also her only possibility for salvation. If she fails to find what she seeks, she is doomed. We watch her desperation through her searching eyes, so that Gravity, to paraphrase Martin Scorsese, is about what is in the frame and what is out of it.

There is a moment in William Gibson’s Neuromancer in which the main character, Case, digitally jacks into the sensorium of his female cohort, Molly Millions. He can see what she sees and feel what she feels, but cannot control her movements. This is the frustration and delight that differentiates the use of long takes and first-person view in Gravity from similar visual techniques in videogames. Dr. Ryan’s hopelessness is affecting precisely because we cannot do anything to improve her situation, despite sharing her perspective. We fall just short of being real participants in the drama. Gravity flirts with the limits between interactivity and observation. It could even be said that a videogame like Dear Esther is doing the same, except the other way around, starting from an interactive medium and then reducing the amount of interactivity until we can only gaze contemplatively and listen for fugitive whispers. Gravity is a film, so it does not have a choice in the matter. We can only gaze and listen. Yet, with its 3D imaging, it encourages audience members to picture themselves reaching for those ropes and handholds along with Dr. Ryan. Action movies have always attempted to bridge the gap between viewers and heroes. Now, this attempt is even more explicit, and the popularity of videogames means that certain aesthetic choices are irreparably associated with the new medium. Lady in the Lake might have done it in the 40s, but visual first-person storytelling reached critical mass thanks to videogames like Doom and Wolfenstein 3D. So, when we adopt Dr. Ryan’s viewpoint, like Case in Molly’s body, we expect to interact but can only observe.

All of this said, most of Gravity is not spent inside the protagonist’s head. Nevertheless, the infrequent editing means that the camera always seems to preserve a continuous physical presence, whether or not it’s actually anchored to Dr. Ryan. The camera is there, and by extension, so are we. Bodies work differently in space, of course. And as the camera masters the constraints and challenges of this setting, so do we as spectators. According to some game theories, when our bodies are located inside the game space, they are redefined in terms of the rules. In soccer, for instance, we must rethink our bodies to only use our feet (3). Videogames follow this logic, and the first hours of most videogame are usually taken up by our gradual reeducation, as we fit into the mold of our digital avatars.

All of this said, most of Gravity is not spent inside the protagonist’s head. Nevertheless, the infrequent editing means that the camera always seems to preserve a continuous physical presence, whether or not it’s actually anchored to Dr. Ryan. The camera is there, and by extension, so are we. Bodies work differently in space, of course. And as the camera masters the constraints and challenges of this setting, so do we as spectators. According to some game theories, when our bodies are located inside the game space, they are redefined in terms of the rules. In soccer, for instance, we must rethink our bodies to only use our feet (3). Videogames follow this logic, and the first hours of most videogame are usually taken up by our gradual reeducation, as we fit into the mold of our digital avatars.

Gravity offers a similar kind of game. Characters must deal with situations they would never encounter on Earth. In fact, one of the movie’s themes is just how alien perceived “weightlessness” really is, and how it requires a radical readjustment (4). Dr. Ryan, worn down by the lingering memory of her dead child and the unremitting danger of her orbital voyage, looks for a reason to continue her struggle and live. Her path towards deliverance requires her to learn how to operate her body in space. She must be reborn – and an image of her floating in fetal position, a window framing her in an artificial womb, reinforces this reading – as a new individual. As the movie opens, she is introduced as a Mission Specialist who has received very little training compared to other astronauts. Gravity, then, chronicles her final and most brutal phase of training. Like a child learning how to carry its weight, she must reassess her body and its capabilities. The emotional and philosophical trajectory of Gravity follows her learning curve. Her helpless infancy, kicking and screaming into the void, gives way to mature and precise navigation (with a fire extinguisher). Finding her place in the universe means knowing how to make her body interact meaningfully with her surroundings. Not doing so means turning into nothing, a vanishing dot in the black background.

- (1) There are exceptions. In some online first-person shooters, when you die during a match and have to wait for the next round to begin, you can make the camera fly around the arena while the current bout unfolds. Also, in real time strategy games, the camera is similarly not chained to the characters, though it is (usually) fixed to a single perspective plane.

- (2) I’m referring to Spacewar! This wasn’t the first videogame, strictly speaking, but it was probably the first killer app. Earlier proto-videogames had been curiosities. Spacewar! developed something like a cult following among the few who had access to computers in the late 60s and early 70s.

- (3) Altuğ Işığan, “The production of subject and space in videogames,” Game: The Italian Journal of Game Studies (2013): accessed October 23, 2013, URL: http://www.gamejournal.it/the-production-of-subject-and-space-in-video-games/#.UmkPr_kbLng. Inspired by Barthes’ studies on myth, the author picks football as his example: “Humans, physics and objects that have been borrowed are still real to some extent; however, humans only gain functionality by pretending not to have any hands, and gravity has gained new functionalities by being put into the service of the fictional universe of the game.” Işığan proposes that games function like “second-order languages,” which use signifiers from a “first-order language” – like hands, feet, the force of gravity, all of which have meaning in our real everyday world – and then “strip them from their already existing signifieds, thereby turning them into empty forms (signifiers), and associate them then with the set of signifieds of its own symbolic order.” That is, hands, feet, and the force of gravity lose their “real world” meanings and gain a new set of meanings in the context of the game. Işığan’s thesis is broader and more detailed than what I put forth here, of course.

- (4) Of course, bodies in orbit are not really weightless. They’re falling around the earth, just not into it.

Related Posts

Guido Pellegrini

Latest posts by Guido Pellegrini (see all)

- The Game of Gravity - October 24, 2013

- Review: Foosball (2013) - October 10, 2013

- The Trilogy of Before Sunrise, Sunset, and Midnight - August 14, 2013

-

altug isigan