Cork Film Festival Review: Halley (2012)

Cast: Alberto Trujillo, Hugo Albores, Luly Trueba

Director: Sebastian Hofmann

Country: Mexico

Genre: Drama | Horror

Official Website: Here

Editor’s Note: The following review is part of our coverage of the Cork Film Festival. For more information on the festival visit corkfilmfest.org or follow the Cork Film Festival on Twitter at @CorkFilmFest.

“Illness and sin are one” is what’s intoned by a preacher at the halfway point of Halley, a horror movie that’s wholly committed to rendering in realist terms the life—or is that death?—of a zombie. If that sounds like material for a comedy, it shouldn’t; much as Harold’s Going Stiff proved with warmth and wit how these cadaverous characters can be played for laughs, it’s much more the concern of Mexican director Sebastián Hoffman to exploit the idea of zombification for a psychological and philosophical study of our relationship to death. No doubt his protagonist Beto would dispute the preacher; the state of prehumous decay in which he starts the movie is nothing if not punishment without provocation.

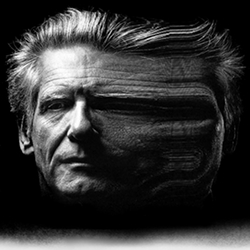

Paramount to the film’s eerie existentialism is the performance of Alberto Trujillo, an extraordinary actor whose wretched physique and ravaged face telegraph the terrifying revelation of bodily decay to come.

Paramount to the film’s eerie existentialism is the performance of Alberto Trujillo, an extraordinary actor whose wretched physique and ravaged face telegraph the terrifying revelation of bodily decay to come. Silent more often than not, it’s through his breathing and the way he carries himself—or indeed fails to do so—that the character is created and his corrosion conveyed. As much admiration is due the make-up team, it’s more Trujillo’s morose mannerisms that convey the extent of his agony. It’s evidently as much psychological pain as it is physical: to decompose without dying, it’s fair to assume, is an awkward invocation of identity crisis; this character is not so much thrust into asking who, but more prominently what and why.

C’est la vie, as any able-bodied atheist will gladly tell you, but to imagine faithlessness brings fearlessness is to forget the mundanity with which mortality takes hold in an irreligious reality. Hoffman’s single church-set scene, that in which the crucial quote is uttered, is essential to the film’s philosophy. Overexposed to a point of unmissable irony, the saintly sheen that bathes the congregation touches all but Beto, who remains drowned in the same darkness that shades him throughout the movie. He faces fatality free of the comfort of Christ; death is his only afterlife, a fact frighteningly manifested in his becoming the walking dead. “You could burn, turn to ashes, and still exist,” suggests a coroner in whose morgue he awakens one day. Would that he could believe in a god instead.

Favouring an aloof aesthetic that might easily be called clinical, he drowns his frames in darkness when he isn’t showcasing their symmetry, making of Beto’s home an impersonal and empty space despite the objects therein.

But benevolent beings seem beyond belief indeed in the world Hoffman here constructs. Favouring an aloof aesthetic that might easily be called clinical, he drowns his frames in darkness when he isn’t showcasing their symmetry, making of Beto’s home an impersonal and empty space despite the objects therein. Plastic-clad furniture and sparkling silverware give the impression of a life never lived but presented as though it were. And that’s an aspect that extends beyond Beto, too: the gym at which he serves as security guard, its sickly lighting ill-distinguished from that of the morgue, plays host to bodies fine-tuned for appearance’s sake; the bus he takes home, its sombre occupants each engaged only with themselves, cake make-up on their faces to offer the illusion of youth.

Hard as Hoffman and Trujillo may work to make a hauntingly hollow being of Beto, his decline is ultimately only an immediately more visible incarnation of our own. We’re each every day trudging closer toward death, perhaps not with so much vulgarity and visibility, but with at least the same sense of certainty about it all. Creepy as the cinematography might make it, eerie as the score’s refrigerator-like hums are, it’s evident that Halley’s relentless realism is there because it is all real. “It feels like it’s always been like this,” laments Beto as he sits naked before the coroner, whose comfort in talking so candidly to a dead man is indication enough of exactly how lifelike he—and it—is.

Related Posts

Ronan Doyle

Latest posts by Ronan Doyle (see all)

- Cork Film Festival 2013: Diary Three - November 14, 2013

- Cork Film Festival Review: Kid (2012) - November 14, 2013

- Cork Film Festival Review: Halley (2012) - November 13, 2013