Subversive Saturdays: Innocence Unprotected

We continue our Subversive Saturdays series with a film that defies conventional classification. It comes from one of my favorite directors, Dusan Makavejev, and he uses the film to illustrate the importance of the medium and the truths that lie in the subtext. These truths will only expose themselves to those willing to dig deep enough to find them. Innocence Unprotected is both the name of the film by Dusan Makavejev, as well as the film that Makavejev is exploring in his unconventional documentary approach. He uses found footage elements, historical documentary footage, new documentary footage, and any bits and pieces that would be useful in the telling of this story.

The telling of a multi-faceted story requires a multi-faceted director. Makavejev is capturing the importance of film as an anthropological time capsule; he is capturing the importance of the lies and escapism that the viewer desperately needs, he is capturing a seldom seen perspective on the events of World War II and how it impacted life in Yugoslavia and Serbia, and he is capturing what film exposes to those with the contextual framework to be able to see the truths that are only found through the perception of purposeful omission. Makavejev’s unique style allows us to see all of these elements, even without the need for firsthand experience. By showing us the importance in this film that was nearly lost, he brings significance to his own film as the mechanism for telling a previously untold story.

The original Innocence Unprotected is not a “good” film by conventional definition. It is seemingly a silly and one-dimensional melodrama, and one would be hard pressed to find artistic significance in its poorly executed populist narrative and bland film-making techniques. By constructing layers of meta-narration and contextualizing the film, Makavejev shows us that perhaps the film holds a profound significance that we otherwise would have been unaware of. He uses uninterrupted sequences from the original film and works in documentary material and historical footage to flesh out the societal conditions at the time that the original film was made. A character in the original Innocence Unprotected stops for a moment to daydream, and their daydream becomes footage from the real world conditions of war, death, and destruction. Seeing this horrific imagery serves to illustrate a certain triviality and silliness in the original film, but as even more layers of meta-narration are added we begin to see significance where none was previously found.

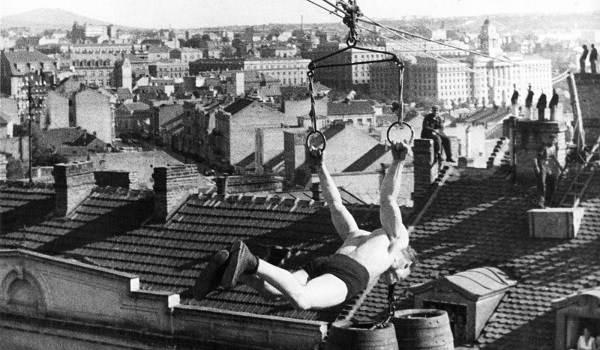

The highlighting of the filmmaker of the original Innocence Unprotected is a prime example of finding profound significance in the subtext. Dragoljub Aleksic wrote, produced, directed, and starred in the original Innocence Unprotected, and he is an integral part of Makavejev’s exploration. We are introduced to him through fetishistic and obsessive camera techniques that explore his muscular physique. As he speaks, we are instantly taken in by his infectious personality, but can see the hucksterism in his persona. He’s a showman straight from vaudevillian traditions, and he carried on his strongman stunts well past his prime and well after doctors had indicated that he wouldn’t have use of his legs due to a severe spinal injury. He is shown both through the archival footage of his original film, and through Makavejev’s 1968 documentary footage. Dragoljub does not strike one as a subversive artist or visionary, but his affable exterior betrays the significance of the man and his efforts.

We eventually discover that the original film was made under Nazi occupation, and we are given a whole new perspective on what seemed like a ridiculous melodrama with bad special effects. Knowing Nazi Germany’s attitudes and their concept of a “master race” and insistence on their own superiority, Dragoljub’s fetishistic and narcissistic shots of himself begin to take on a profound and subversive significance. He is using himself as an example to undercut the Nazi concept of a master race, and he is doing so illegally and during Nazi occupation. Suddenly this addition of a meta-narrative context unlocks new truths in the original film. What once seemed like a conventional yet poorly made melodrama now takes on new meanings as a weapon against a superior occupying force. The narcissistic shots that litter the entire film now open up as a subversion of Nazism and we find out that Dragoljub risked his life to create the film during the occupation.

What can we take away from this exploration? We have perhaps learned that art is larger than man, larger than criticism, and that what looks like a second class effort of expression can be the carrier of profound truths and revolutionary subversion if one has the historical knowledge to contextualize not only that which occupies the screen, but also that which is strategically omitted. We may have learned that film holds significant value as a societal preservation mechanism, and that it has a great deal to show us if we explore it deeply enough. In any case, Makavejev’s Innocence Unprotected is a phenomenal film from a truly unique voice, and my historical context has been broadened as a result of having watched it.

Review: Funny Games (2007)

Review: Funny Games (2007) Review: Osaka Elegy (1936)

Review: Osaka Elegy (1936) Review: Miss Bala (2011)

Review: Miss Bala (2011) Review: Hidden (2005)

Review: Hidden (2005) Review: Watching TV With The Red Chinese (2012)

Review: Watching TV With The Red Chinese (2012)