Subversive Saturday: The Blood of a Poet (1932)

Cast: Stepan Shkurat, Elizabeth Lee Miller, Pauline Carton

Director: Jean Cocteau

Country: France

Genre: Drama | Fantasy

Official Trailer: Here

Editor’s note: The following review is a continuation of Matthew Blevins’ Subversive Saturdays series.

“The three most subversive aesthetic tendencies of our century – surrealism, expressionism, and dada – are anchored in the reality of a civilization in decline. They are gestures of defiance against the chaos which is organized society. “ –Amos Vogel, Film as a Subversive Art

This week we will be exploring the “Aesthetic Rebels and Rebellious Clowns” chapter of Film as a Subversive Art with Jean Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet. Vogel does not classify The Blood of a Poet as a surrealist work, but rather a conscious poetic deconstruction of time, space, and perceptibility. Surrealism is the unfettered and unmanipulated expression of subjective truths through imagery that is not intended to be interpreted in any objective fashion, whereas Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet gives clues that can lead one to certain conclusions. It is a puzzle that Cocteau openly invites us to decrypt through text during the opening credits. Classifications can be silly in their reductive and pedantic nature as critics and historians argue about which piece of art fits where and why, but they can be helpful in capturing common threads that run through the bodies of work of a diverse group of artistic peers. While there may have been objective conclusions that could be deciphered from Cocteau’s series of abstract tableau vivants, it conveys these obfuscated ideas using non-objective imagery that provokes and attacks the aesthetic expectations of the mainstream observer.

Surrealism is the unfettered and unmanipulated expression of subjective truths through imagery that is not intended to be interpreted in any objective fashion, whereas Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet gives clues that can lead one to certain conclusions.

One such manifestation of aesthetic rebellion is the way in which Cocteau accomplishes his gravity and logic defying feats with the alienating use of untrustworthy camera positioning. The casual film viewer will accept the objectivity of any images placed before them because of the expectations established by conventional films they had seen before. In The Blood of a Poet, that relationship is subverted as the camera tilts with entire rooms to create the visual effect of a man climbing up walls and travelling in physically impossible directions. We are forced to recognize that what we perceive is a lie. It is merely trickery employed to create a rift between audience and artist, and the sacred trust between them has been torn asunder as we can no longer accept the objectivity of any image that we see on the screen. We are forced to either relinquish our socially prescribed affinity toward what Werner Herzog calls “the accountant’s truth”, or suffer in indignant alienation, so comforted by our laughably limited perception that we are unable to accept the intentionally alienating perversions from the poetic mind.

One such manifestation of aesthetic rebellion is the way in which Cocteau accomplishes his gravity and logic defying feats with the alienating use of untrustworthy camera positioning. The casual film viewer will accept the objectivity of any images placed before them because of the expectations established by conventional films they had seen before. In The Blood of a Poet, that relationship is subverted as the camera tilts with entire rooms to create the visual effect of a man climbing up walls and travelling in physically impossible directions. We are forced to recognize that what we perceive is a lie. It is merely trickery employed to create a rift between audience and artist, and the sacred trust between them has been torn asunder as we can no longer accept the objectivity of any image that we see on the screen. We are forced to either relinquish our socially prescribed affinity toward what Werner Herzog calls “the accountant’s truth”, or suffer in indignant alienation, so comforted by our laughably limited perception that we are unable to accept the intentionally alienating perversions from the poetic mind.

The casual film viewer will accept the objectivity of any images placed before them because of the expectations established by conventional films they had seen before. In The Blood of a Poet, that relationship is subverted as the camera tilts with entire rooms to create the visual effect of a man climbing up walls and travelling in physically impossible directions.

The mirror is a symbol that Cocteau would explore many times through his body of work. It is a perfect illustration of the imperfect nature of our own perception, and shows us how we willfully adopt lies as canonical truths. We are incapable of perceiving ourselves as others do because of the mirror’s inversion of reality, but we still accept its images as trustworthy, and even adopt them in our mind’s flawed inventory of imagery. The mirror acts as a means of transportation for the poetic soul to travel to a realm of unmitigated creativity. It is a realm of death in Cocteau’s later “Orphic” films, but an artist must confront their own mortality with maddening regularity if they are to understand and create representations of facets of the human condition.

The mirror is a symbol that Cocteau would explore many times through his body of work. It is a perfect illustration of the imperfect nature of our own perception, and shows us how we willfully adopt lies as canonical truths. We are incapable of perceiving ourselves as others do because of the mirror’s inversion of reality, but we still accept its images as trustworthy, and even adopt them in our mind’s flawed inventory of imagery. The mirror acts as a means of transportation for the poetic soul to travel to a realm of unmitigated creativity. It is a realm of death in Cocteau’s later “Orphic” films, but an artist must confront their own mortality with maddening regularity if they are to understand and create representations of facets of the human condition.

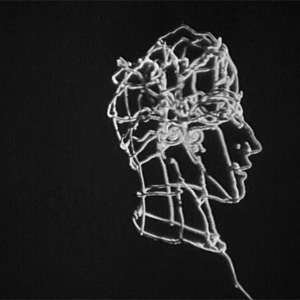

Cocteau fixates on images and their reverse in the aim of illustrating our imperfect perception as we misinterpret relief and counter-relief images as a mask spins at the center of the screen, one side symbolically painted with the Judeo-Christian interpretation of divinity, the other with pagan symbols from early forms of mysticism. They are two sides of the same coin, guiding humanity through the deconstruction of the unearned certainty we place on our limited perception when we are unable to determine if what we are looking at is the concave or convex side of the mask until we view it from a profile vantage. Cocteau uses this illusion many times throughout the film, often using rotating wire sculptures of three-dimensional objects to accomplish this disorienting effect. The poetic mind is ill at ease with granting objective certainty to any thought or image because this mind is acutely aware of its own limitations. The overabundant rationalists of the world either choose to ignore these discrepancies or are blissfully ignorant of their existentially maddening implications.

The poetic mind is ill at ease with granting objective certainty to any thought or image because this mind is acutely aware of its own limitations.

Other forms of dutiful alienation occur with the lack of synchronized sound which is replaced by musical embellishments and poetically ambiguous narration. These elements combine to create an unsettling disconnect between image and sound that forces the viewer to accept the metaphysical qualities of the images as they have no basis in our own physical reality. These are the illogical transmissions of the subconscious mind, and Cocteau employs a multidimensional approach to aesthetic subversion in his beautifully futile attempt to document the unquantifiable. He also attacks the audience directly, as bourgeoisie socialites look down from the safety of their extravagant balcony seats at the negotiation for a boy’s soul with disinterest and boredom. They only came to be part of the scene or to be noticed by other socialites so they can all feel self-righteous for their patronization of the arts.

Other forms of dutiful alienation occur with the lack of synchronized sound which is replaced by musical embellishments and poetically ambiguous narration. These elements combine to create an unsettling disconnect between image and sound that forces the viewer to accept the metaphysical qualities of the images as they have no basis in our own physical reality. These are the illogical transmissions of the subconscious mind, and Cocteau employs a multidimensional approach to aesthetic subversion in his beautifully futile attempt to document the unquantifiable. He also attacks the audience directly, as bourgeoisie socialites look down from the safety of their extravagant balcony seats at the negotiation for a boy’s soul with disinterest and boredom. They only came to be part of the scene or to be noticed by other socialites so they can all feel self-righteous for their patronization of the arts.

The most jarring alienation in the film occurs when we discover the complete subversion of cinematic time when the crumbling chimney at the beginning of the film is abruptly shown crashing down in the final frames. With this visual callback, Cocteau accomplishes one last bit of profound audience alienation when we are forced to contend with the subjectivity of our ability to perceive time, and we must now reassess everything we had seen before. Even if we learned to overcome our need to logically solve every ambiguous image and sound that presents itself to us, we could still find comfort in the incorruptibility of time. When we learn that the events of the film may have unfolded in mere seconds, we are forced to reassess our interpretation of what we have perceived. The mind’s need to classify and quantify everything it perceives is a safety measure to help avoid staring directly into the existential void without guard rails to keep us from falling in.

The poet jumps headfirst into their own existential void with reluctant willfulness to try to climb out with just enough information to mediate an understanding of that void with those incapable of such introspective exploration. It is a maddening and self-destructive process, but the poet must suffer so that the rest of humanity can learn from their discoveries. The poet will meet resistance as they try to convey the message because the human mind has a hard time tangling with unresolved questions. Mainstream consciousness tries desperately to fill these holes with easy stopgap fixes, but the poet continually picks at these wounds to expose the festering idiosyncrasies of easy answers and too much certainty in one’s limited perception. It is both a curse and the divine responsibility of the poetic mind to engage in this underappreciated introspective pioneering, even at the cost of sanity and blood.

-

http://twitter.com/adam_the_k Adam K

-

http://twitter.com/TheBlevo Matt Blevins

Review: Blood of My Blood (2011)

Review: Blood of My Blood (2011) Review: Damsels in Distress (2011)

Review: Damsels in Distress (2011) DVD Review: My Perestroika (2010)

DVD Review: My Perestroika (2010) Subversive Saturday: The Blood of a Poet (1932)

Subversive Saturday: The Blood of a Poet (1932) Review: Dark Shadows (2012)

Review: Dark Shadows (2012)