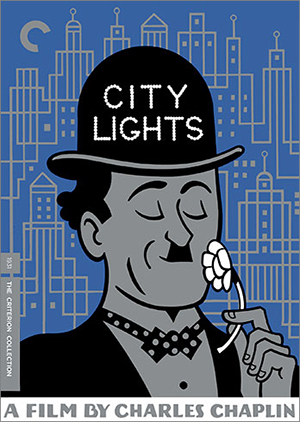

Blu Review: City Lights (1931) - NP Approved

Chaplin’s 1931 masterwork City Lights opens, appropriately enough, with a title card labeling it a “Comedy Romance in Pantomime,” a distinction that extols its status as a silent picture in an era fastly falling smitten with diegetic sound. But the word “pantomime,” naturally, carries with it other implications aside from a cinematic form of expressive gesticulation. Chaplin’s signature character, The Tramp, is also but a creature of imitation and role-playing, his mannerisms, however polite and well meaning, clearly parroted from more high society citizens. From the opening scene – a delightfully prickly scenario set at a statue’s unveiling – the friction inherent to such a bipolar class system is present, with The Tramp acting as a surrogate for, if not the desolately impoverished, those socially marginalized by economic difference; the character’s mere presence is a reminder to the glitterati that poverty persists despite their gentrifying efforts. Throughout City Lights, Chaplin amusingly illuminates how elitism permeates societal custom, as there’s little mistaking Chaplin’s tatter-clothed protagonist as anything beyond a kindly guttersnipe, no matter how courteously he might tip his bowler or how playfully he might twirl his cane.